Introduction

Background

Negative emotions and adversities are common in daily life, yet some people tend to cope better than others. The capacity to adapt and bounce back from adverse experiences is termed resilience, for which there is no universally agreed definition. Vella, Pai, et al. (2019) frames resilience as a process involving both the occurrence of adversity and the mitigation of its effects to produce positive outcomes. From a process perspective, it is useful to distinguish resilience as a trait from resilience as a state. Trait resilience is a stable psychological characteristic, while state resilience is an adaptive response that varies with context and time. An alternative, outcome-based perspective, views resilience as the achievement of positive adaptation in the face of risk. This proposal begins by defining the boundary of adversity and positive outcomes, conceptualizing resilience, outlining how resilience will be measured, to identifying key research issues relevant to its role as a moderator in the relationship between stress and mental health.

The Definition of Adversity and Positive Outcomes

This study refers to adversity as the presence of challenging or harmful circumstances that require psychological adaptation. Conceptually, adversity is the interface between external risk factors and the individual’s subjective experience of difficulty (Vella, Pai, et al. 2019). While adversity can be examined in terms of statistical associations between adverse life events and adjustment, it may also be identified without a formal statistical threshold, for example through self-reported experiences of significant difficulty. In this study, adversity is quantified as the degree of perceived difficulty, implying adversity as an ongoing or recurrent challenge in daily life (Vella, Pai, et al. 2019). Perceived difficulty will be measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), which has been adapted and validated for use in the Indonesian population.

Positive outcomes are defined as indicators of successful adaptation following adversity, such as maintaining, regaining, or surpassing prior levels of psychological and social functioning. Following Vella, Pai, et al. (2019), a positive outcome may include prevention of mental illness, reduction in symptom severity, or sustained subjective well-being despite exposure to risk. Our study operationalizes positive outcomes as lower levels of depression, anxiety, and burnout. Each outcome will be measured by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety, and Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) for burnout, which have also been adapted and validated for use in the Indonesian population.

The Definition of Resilience

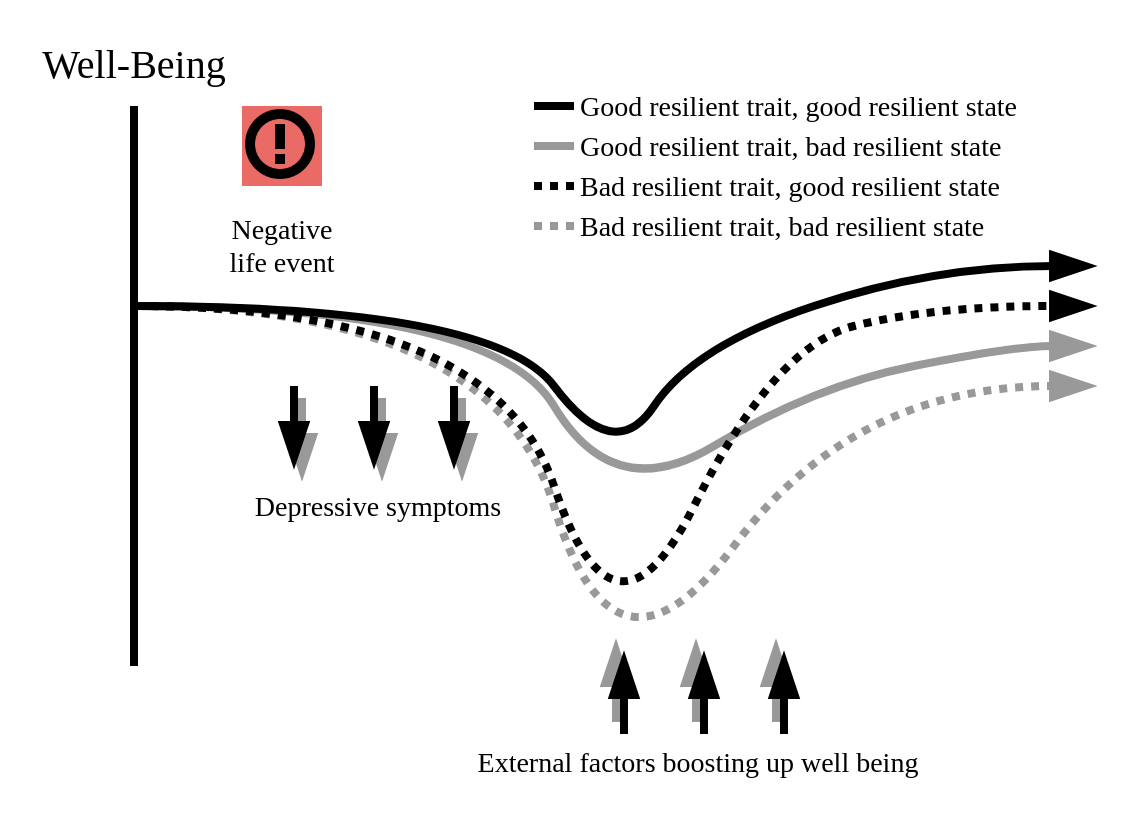

Building on the definitions of adversity and positive outcomes, resilience refers to the capacity to adapt effectively to negative setback in life. Bonanno (2008) distinguishes resilience from recovery: recovery implies the presence of pathological symptoms that gradually dissipate over time, whereas resilience describes the ability to maintain well-being equilibrium in the face of adversity. Importantly, resilience is distinct from merely the absence of psychological problems. Resilient individuals may experience temporary perturbations in daily functioning, such as sporadic preoccupations, restless sleep, or transient sadness, without developing a disorder.

Infurna and Luthar (2016) notes that resilience can also be observed in individuals recovering from psychological disorders, suggesting that resilience functions both as a stable trait and as a dynamic state that facilitates recovery. Both Bonanno (2008) and Infurna and Luthar (2016) conceptualize resilience along a continuum, where trait resilience establishes a baseline threshold against adversity, and state resilience serves as a dynamic buffer connecting baseline capacity to recovery outcomes. Luthar, Cicchetti, and Becker (2000) emphasizes the importance of defining resilience as a trait or state, proposing the state of resilience as “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity.”

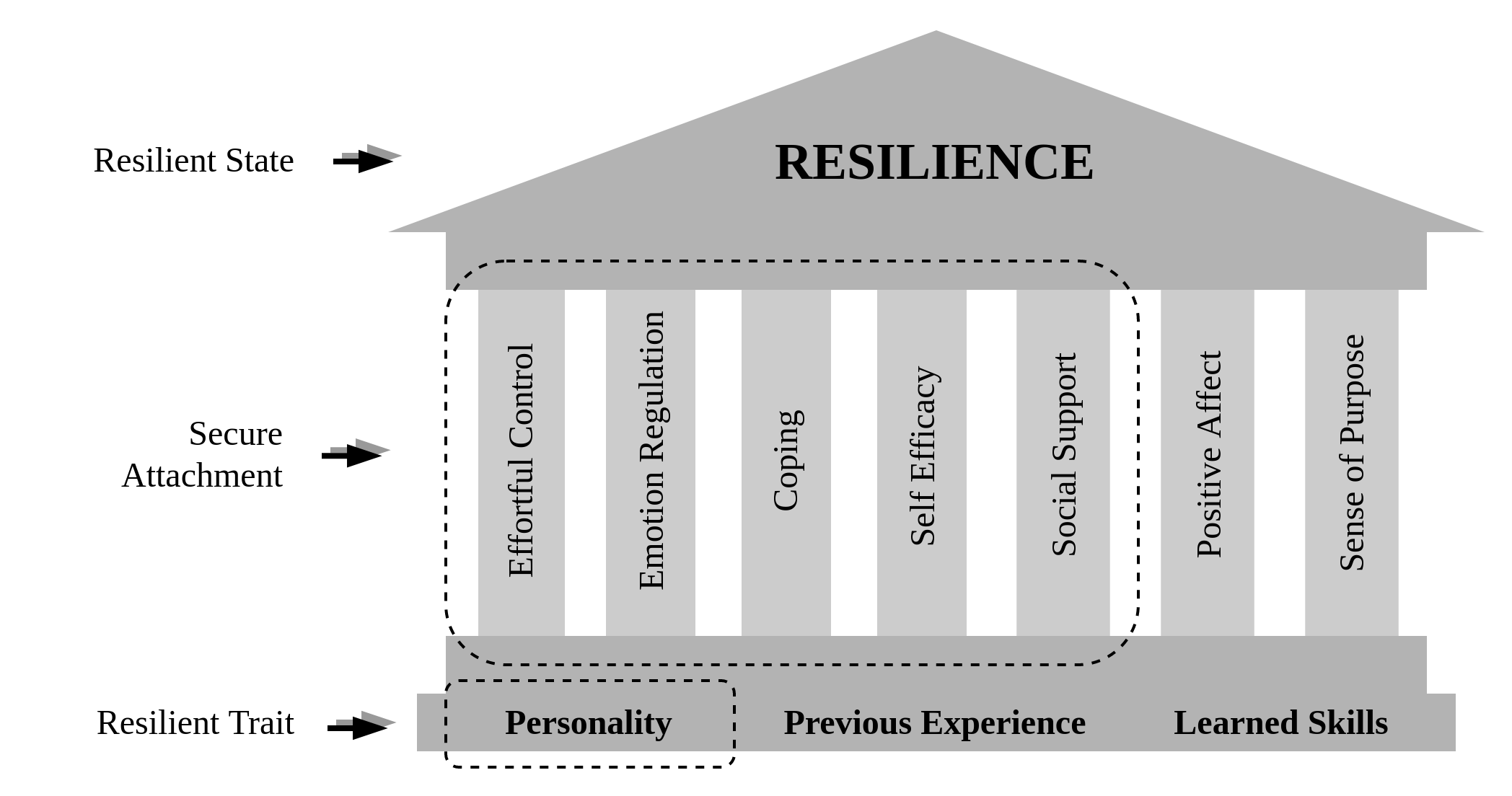

To illustrate these concepts, Figure 1 presents a hypothetical model of how trait and state resilience contribute to the trajectory of well-being over time. In this model, trait resilience represents the underlying psychological capacity to withstand adversity, while state resilience functions as a buffer that promotes recovery and adaptation when negative setbacks occur. These theoretical distinctions guide the operationalization of resilience in this study, linking conceptual understanding to measurable constructs.

Constituents of Resilience

Resilience is supported by three interrelated psychological factors, namely secure attachment, positive emotions, and a sense of purpose in life (Rutten et al. 2013). These factors form the foundation of mental health, helping individuals maintain well-being when facing adversity and facilitating the recovery process. Secure attachment, established through early caregiver-child interactions, provides children with an internal working model for interpreting social relationships and managing emotions (Atwool 2006). Positive emotions enhance coping capacity, build trust, and strengthen life satisfaction even under stress (Cohn et al. 2009; Waugh 2020). Meanwhile, a sense of purpose fosters well-being, guiding personal growth and promoting optimism (Kaczmarek 2017; Kim, Salstein, and Goldberg 2021).

Secure attachment emerges during early childhood as a product of consistent, responsive caregiving, forming an internal working model that guides how children perceive themselves, others, and the environment (Rutten et al. 2013; Atwool 2006). Children with secure attachment tend to see themselves as worthy, others as reliable, and challenges as manageable. This internal model facilitates the effective self-regulation, emotional understanding, and social competence, which are critical for navigating adversity. As the internal model consolidates by around age five, it continues to influence the child’s capacity to respond adaptively to stress and develop resilience throughout life. Secure attachment empowers children with self-regulation, empathy, and the capacity to manage interpersonal relationships (Atwool 2006).

Positive emotions play a crucial role in psychological well-being and resilience, often outweighing the impact of negative emotions in promoting mental health (Rutten et al. 2013; Cohn et al. 2009). Experiencing positive emotions, even temporarily, enhances trust, compassion, and adaptive coping, also strengthens the link between resilient traits and life satisfaction (Cohn et al. 2009; Nylocks et al. 2018; Waugh 2020). Positive emotions also buffer the perception of adversity, facilitating recovery from stress (Waugh and Koster 2015). While individual differences exist, these variations are modest once social and interpersonal stressors are accounted for. In sum, cultivating positive emotions supports coping processes and contributes to the development and maintenance of a resilient state (Tugade and Fredrickson 2006).

Beyond secure relationships or moments of happiness, having a clear and enduring purpose in life promotes a deeper and more lasting contribution to resilience (Rutten et al. 2013; Kaczmarek 2017). Such a purpose gives direction, encourages the pursuit of personally meaningful goals, and supports the development of the innate potential. Over time, maintaining the sense of purpose contribute to well-being by fostering optimism and lowering the risk of depression and loneliness (Kim, Salstein, and Goldberg 2021). When individuals feel connected to their values and life direction, religion and spirituality can play an important role in reinforcing resilience, particularly for those who have limited opportunities for social interaction (Chan, Michalak, and Ybarra 2018; Rutten et al. 2013). While the drive to find meaning in life is unique to each person and often deeply personal (Disabato et al. 2016), it does not depend solely on internal reflection. Shaping one’s surroundings to encourage purposeful action can also strengthen resilience and help maintain a coherent sense of self and the world (Rutten et al. 2013).

Considering resilience as a dynamic psychological state, several factors contribute to its development. Precious and Lindsay (2019) proposed seven main pillars supporting resilience, which can be derived from the three psychological factors introduced by Rutten et al. (2013). In Figure 2, five pillars are attributed to secure attachment, while the remaining two reflect positive emotion and purpose in life, respectively.

First, secure attachment between children and parental figures positively correlates with resilience (Gilliom et al. 2002; Viddal et al. 2015; Shi et al. 2020), mediated by the development of effortful control. Effortful control is a volitional ability to generate adaptive responses that reflects self-regulation. Children with secure attachments are more likely to develop effective self-regulation, which reduces tendencies toward aggression (Stifter, Putnam, and Jahromi 2008; J. Liu 2004). While Gilliom et al. (2002) observed this association primarily in boys, Shi et al. (2020) demonstrated that in adults, gender differences in self-regulation are minimal, suggesting that early secure attachment fosters self-regulatory capacities across gender in later life (Heylen et al. 2016). Longitudinal research indicates that effortful control in early adolescence correlates with resilience at each time point, although both traits may fluctuate over time (Nair et al. 2020; Eisenberg et al. 2009). Collectively, secure attachment promotes the consolidation of self-control, which serves as a foundation for resilient behaviors.

Second, emotion regulation is a central component in developing resilience that is deeply influenced by the quality of attachment between children and their caregivers (Cassidy 1994). From the first year of life, children begin to form internal working models based on their interactions with caregivers. Internal working model is a mental representations of how the world responds to their emotional needs. Securely attached children learn to expect that their feelings will be acknowledged and supported. This reliable responsiveness encourages children to express and discuss their emotions openly, fostering the development of effective strategies for managing emotional responses from caregivers. Those with avoidant attachment tend to repress emotions and recall negative experiences in a muted way, while children with anxious attachment vividly remember negative events and remain preoccupied with them (Bowlby 1973; Hinde and Lorenz 1996; Bretherton 2013; Mikulincer and Shaver 2019). Both avoidant and anxious attachment patterns are associated with fragile emotion-regulation abilities and a reduced capacity to cope with prolonged or uncontrollable stressors. Emotion regulation develops as a specialized skill that integrates both child’s temperament and child-parent attachment, allowing children to exercise attentional control and cognitive reappraisal to manage emotional responses. By reducing the intensity and duration of negative emotion, these strategies help maintain psychological balance and contribute to the emergence of a resilient state (Kay 2016).

Third, effective coping fosters psychological growth by enabling individuals to adapt through consistent exposure to daily stressors. The emergence of a resilient state depends not only on the availability of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but also on the experience of manageable stress that actively strengthens regulatory capacity (DiCorcia and Tronick 2011). A gradual exposure to such stressors challenges individuals to push their limits, and in turn fostering endurance and more effective coping skills. This process provides opportunities to practice adaptive responses that incrementally improve resilience. Within this dynamic, positive emotions plays a critical role in reconciling negative emotions during moments of stress, thereby facilitating the use of mature coping strategies (Ong et al. 2006). In addition, adaptive self-reflection serves as a key mechanism for reinforcing resilience. This reflective practice involves five sequential steps, namely cultivating emotional awareness, identifying trigger, reappraising the stressor, evaluating the response, and adopting a future-oriented perspective (Crane et al. 2018; Goodvin et al. 2008; Hamarta, Deniz, and Saltali 2009). The first three steps focus on understanding and responding to the immediate situation, while the latter two emphasize growth and preparedness for future challenges. Emotional awareness entails recognizing internal shifts in reaction to triggering events. Trigger identification helps establish the causal link between stressors and responses. Reappraisal leverages these insights to frame stressors in a more constructive light, enabling a more goal-aligned reaction. Response evaluation is an emotionally distanced review of the situation aimed at improving the effectiveness of future responses. Finally, future-oriented planning emphasizes actionable strategies to address similar challenges moving forward. Through consistent practice of these processes, individuals not only process adversity more effectively but also sustain psychological stability over time (Tronick and DiCorcia 2015).

Fourth, self-efficacy develops from early-life experiences of secure attachment, which lay the foundation for positive internal working models that guide a positive self-perception. Self-efficacy represents an individual’s belief in their ability to attain desired goals, shaped by self-referent expectations and the capacity for reflective thought (Bandura 1978). Self-efficacy is inherently task-specific, meaning a person may display strong confidence in one domain yet feel uncertain in another. Processing high self-efficacy equips individuals to recover from setbacks, maintain sustained effort under pressure, and respond constructively to negative feedback (Heslin and Klehe 2006). In contrast, low self-efficacy often heightens vulnerability to anxiety or depression, as individuals may interpret feedback through assumptions of incompetence or incapacity. Empirical evidence indicates that both self-efficacy and self-care serve as partial mediators between attachment style and resilience, suggesting that secure attachment fosters a strong, positive belief in personal capability (Bender and Ingram 2018). Confidence in one’s capacity promotes effective behavior, which in turn validates and strengthens that belief (Bandura and Watts 1996). In this way, self-efficacy fuels affective, motivational, and behavioral mechanisms that enable individuals to sustain resilient attitudes and adaptive behaviors amidst challenging circumstances (Schwarzer and Warner 2012).

Fifth, social support is intrinsically linked to social competencies that originate from early child-parent attachment experiences. A secure attachment fosters the development of a positive internal working model of the social environment, which strengthens the belief in the availability and reliability of social support. Conversely, insecure attachment often results in a negative working model, characterized by fear of intimacy and a tendency toward social withdrawal. These working models are foundational to the maturation of social competencies, which Mallinckrodt and Wei (2005) defines as the essential skills for establishing and maintaining supportive social relationships. Two central components of these competencies are social self-efficacy and emotional awareness. Social self-efficacy is the confidence to initiate and cultivate connections from initial acquaintances. Emotional awareness is the ability to recognize and understand one’s own emotions and those of others. Individuals with secure attachment and a positive working model generally display higher levels of these competencies, while those with a negative working model often show deficits in one or both. For example, an anxious attachment style is frequently associated with social uncertainty, a sense of powerlessness, and difficulty sustaining close relationships. In contrast, avoidant attachment may manifest as affective disengagement, where individuals repress emotional perception (Mallinckrodt and Wei 2005). Maintaining strong social ties is critical for securing access to both psychological and material resources, thereby enhancing one’s capacity to cope with adversity (Cohen 2004). As argued by Sippel et al. (2015), social support serves as a moderating factor for genetic and environmental vulnerabilities, enabling individuals to display resilience. Such support fosters stress-regulating behaviors, bolsters self-confidence, encourages mature coping strategies, promotes effective emotion regulation, and strengthens the resilient state.

Observing Trait and State Resilience

Resilience, both as a trait and state, contributes to maintaining psychological well-being by reducing or buffering the negative effects from experiencing adversities. Hu, Zhang, and Wang (2015) characterized trait resilience as more innate and stable, which supports classifying individuals into resilient and less resilient groups. However, measuring resilience only as a trait risks underestimating its occurrence and variability in the population. For example, Gheshlagh et al. (2017) reported high heterogeneity across studies that used instruments such as the CD-RISC1, the RSA2, and the ERS3; this heterogeneity may reflect differences in instruments, study samples, timing of assessment, and contextual factors rather than a single source. Both Gheshlagh et al. (2017) and Hu et al. (2015) noted that higher resilience is associated with lower depression, anxiety, and negative affect.

1 Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; 25 items

2 Resilience Scale for Adults; 33 items

3 Essential Resilience Scale; 15 items

This research focuses on state resilience in favor of policy-making and intervention relevance. State resilience is potentially modifiable and therefore a plausible target for programs intended to reduce the mental health impact of adversity. While trait resilience is valuable for identifying at-risk groups, state resilience offers actionable targets for interventions and mental health policies. Operationally, state resilience will be treated as a time-varying construct and measured with scales that are sensitive to change and validated for the Indonesian context. This is to ensure that the findings can inform strategies to strengthen adaptive responses to stress and adversity.

Key Issues

Resilience refers to the dynamic capacity of individuals to adapt and recover in the face of adversity, shaped by interacting biological, physiological, social, and ecological factors (Ungar and Theron 2020). It encompasses promotive and protective processes such as secure attachment, positive emotion, and a sense of purpose (Rutten et al. 2013). Resilience is supported by mechanisms of homeostatic plasticity and emotional regulation (Vella, Pai, et al. 2019; H. Liu et al. 2018).

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that higher resilience is associated with lower levels of depression, anxiety, and burnout (Hu, Zhang, and Wang 2015). Burnout, which shares overlapping features with depression and anxiety, may represent a converging pathway through which stress affects mental health (Meier and Kim 2022; Koutsimani, Montgomery, and Georganta 2019). In acute crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with greater resilience report less distress and better adaptation to abrupt changes (Barzilay et al. 2020).

In Indonesia, COVID-19 has exacerbated existing mental health challenges, particularly among lower socioeconomic groups (Tampubolon, Silalahi, and Siagian 2021). Even prior to the pandemic, Hanum, Utoyo, and Jaya (2022) reported substantial proportions of older adults with stress (46.3%) and depression (31.7%). Given the high prevalence of mental health symptoms, limited service access, and the potential protective role of resilience, this study seeks to address the central question:

“What is the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of public health policies to maintain mental resilience amidst adversities, especially regarding their impact on depression, anxiety, burnout, and related medication use?”

This research is primarily concerned with examining how variation in resilience may buffer the relationship between stress exposure and mental health outcomes. The findings are intended to inform interventions and policies targeting populations at highest risk of stress-related mental health problems.

Research Questions

Objectives

General Objectives

This research aims to delineate the influence of state resilience as a buffer of general health stressors in eliciting depression, anxiety, and burnout.

Specific Objectives

This research poses five specific objectives, each is focused as a separate investigation:

- Measure the distribution of state resilience in the sampled Indonesian population using a validated instrument.

- Derive outcome-based resilience scores using the residual approach.

- Estimate the association between perceived stress and mental health outcomes, namely, depression, anxiety, and burnout.

- Evaluate whether state resilience moderates the association between perceived stress and each mental health outcome.

- Compare state resilience and outcome-based resilience to assess convergent or divergent validity.

Appeals

This research focuses on the data mining process, especially to generate new insight and knowledge (knowledge mining). The tools used in this research shall be free to access under an open-source license, with some restriction to the source code of a more specific use cases, which will be protected under a closed-source license. The highlight of the proposed model is to use agent-based model as a general modelling framework using a graph object as its input. The following subsections shall further elaborate how the general framework and knowledge mining process can be beneficial for the institution, researchers, and general audiences.

Appeals to the Institution

Firstly, this research aims to disentangle the general framework of agent-based modelling in a graph object. The general modelling framework will be useful in various cases representable as a graph object, especially a knowledge graph. This framework is beneficial for the institution, since a patent for specific use cases would be applicable.

Appeals to the Researchers

Secondly, for researchers, the use of general modelling framework will aid in the modelling workflow. The agent-based model can be treated as a singular building block of an analytic pipeline. This will aid the researchers in generating a more flexible model by incorporating the general modelling framework.

Appeals to the General Audiences

Thirdly, the general audiences will gain benefits from the knowledge mining process. Generally, this research will highlight effective countermeasures against psychological stressors and psychological disorders. Furthermore, this research will yield an insight regarding improving the resilient state.